Wikipedia

You may have escaped your 10th grade summer reading list, but chances are you know exactly what I mean when I utter the words, "She was a total case of Jekyll and Hyde."

An eerie, gothic novella written in 1886 by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson—whose birthday is today—The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has transcended its sordid backstory (more on that in a minute) and become a moniker for anyone and anything with a seemingly split personality—one half good, one half evil.

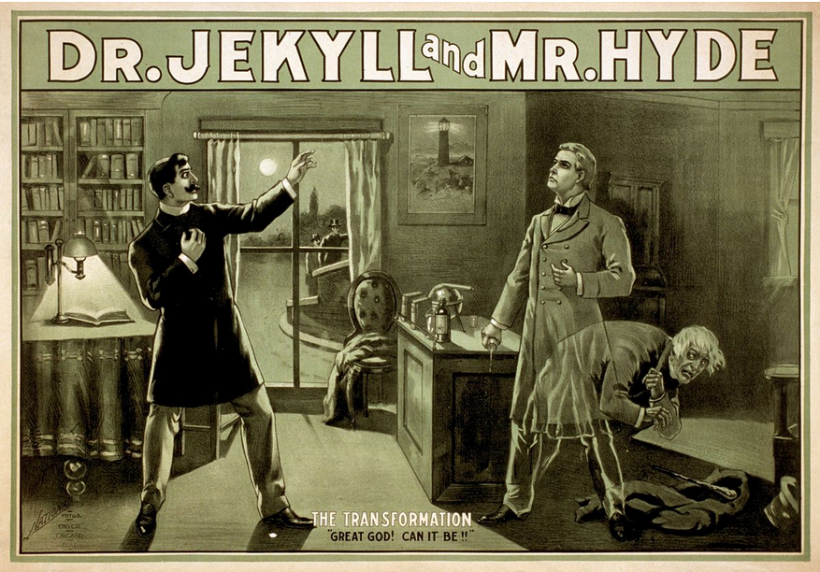

The tale traces the investigation of a London lawyer whose old friend Dr. Henry Jekyll has grown increasingly erratic; it's discovered—say it isn't so!—that Jekyll "transforms" into the dastardly Hyde, murdering and pillaging at will. The transformations begin as intentional—brought upon by a serum of course—but soon enough, Jekyll loses control of his alter ego and devolves in his sleep.

It's an instant classic that catapulted Stevenson to literary fame, saved his family from destitution, and is still considered a pivotal work. But it was thisclose to never seeing the light of day.

The Lurid Backstory Of A Classic Tale

Stevenson was rather sickly his entire life, suffering from what then was believed to be tuberculosis, but what now people believe was Bronchiectasis (chronic lung irritation) and/or Sarcoidosis (another nasty lung disease).

About the age of 36, Stevenson's health was no better; he was largely bed-ridden, delirious and according to some, imbibing a steady stream of amphetamines. The story goes that during a feverish, cocaine-induced nightmare, he saw the entire tale of Jekyll and Hyde in his mind's eye.

His wife Fanny describes the moment of literary revelation: "In the small hours of one morning, [...] I was awakened by cries of horror from Louis. Thinking he had a nightmare, I awakened him. He said angrily: 'Why did you wake me? I was dreaming a fine bogey tale.' I had awakened him at the first transformation scene."

Stevenson began scrawling madly, writing through the entire night and compulsively through the next three days, crafting the entire 30,000-word novel in 72 hours, a feat that to this day is largely unheard of.

But here's where it gets juicy! For decades, the public believed that Stevenson himself had decided to burn his first manuscript:

"... Mrs Stevenson according to the custom then in force wrote her detailed criticism of the story as it then stood pointing out her chief objection that it was really an allegory whereas he had treated it purely as if it were a story In the first draft Jekyll's nature was bad all through and the Hyde change was worked only for the sake of a disguise She gave the paper to her husband and left the room After a while his bell rang on her return she found him sitting up in bed the clinical thermometer in his mouth pointing with a long denunciatory finger to a pile of ashes. He had burned the entire draft." — The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson by Graham Balfour

Balfour explains that Stevenson destroyed his manuscript because he believed the point of view was wrong; he was worried that if he didn't thoroughly dispose of his first draft he'd never truly rewrite the story from the newfound perspective he was after.

More than 114 years later, it was revealed that in fact, it was Fanny who did the dirty deed.

A letter was discovered to Stevenson's close poet friend WE Henley in which she wrote the story was "a quire full of utter nonsense . . . He said it was his greatest work. I shall burn it after I show it to you."

Fanny must have truly believed the horror novel was going to sully her husband's reputation—their life was a blur of creditors and debt; they sorely needed the money from his new novel. "Almost deranged" from chronic sickness and "medicinal cocaine," Stevenson took one look at the ashes and turned right back to the page. He re-wrote the story by hand in another three days.

Despite Fanny's fear and criticism, the novel was received with critical acclaim, and its success snatched them from the jaws of financial ruin. Shortly after its initial publication, stage productions began cropping up across Boston and England, preachers read excerpts on their pulpits as a cautionary tale of morality, and by 1901, it's estimated Stevenson had sold nearly 250,000 copies.